In Just Get HS2 Done, we urged Government to proceed with HS2 Phases 1 and 2a. We were also clear that there are problems with rail services in the North today that need addressing, not in 20 years’ time.

Leaks of the Oakervee Review of the project say that it urges Government to proceed with HS2 Phases 1 and 2a which is most welcome but that it also:

‘recommends that work on Phase 2b of the project from the West Midlands to Manchester and Leeds be paused for six months for a study into whether it could comprise a mix of conventional and high-speed lines instead’. (Source Financial Times, 20th January 2010)

There has been enough dither and delay already. The Oakervee Review was only due to take six weeks – and that was 6 months ago. Looking again at using existing lines (perhaps with upgrades) as alternatives to new high-speed lines has been done repeatedly already by the Department for Transport as part of its oversight of the project. There would be nothing new to learn from a new six-month study to look yet again at the same issue. And Phase 2b is already slated for completion 20 years hence even before any further review is carried out.

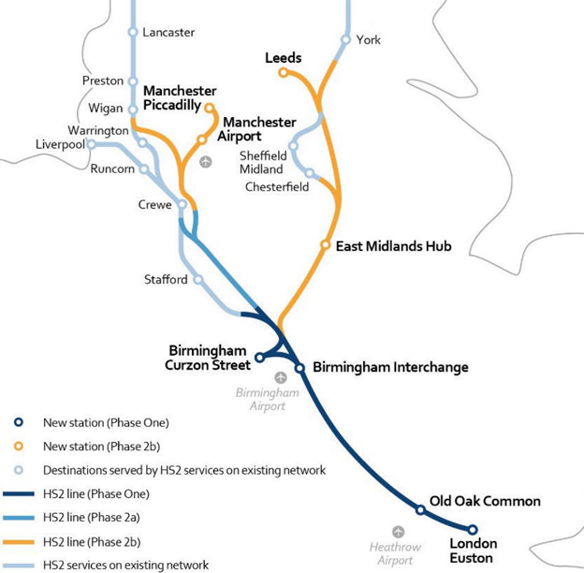

HS2 Phasing Plan

However, it is evident that there needs to be a clear new mandate for Phase 2b and here we set out what it should be. The Oakervee Review expresses doubts about the HS2’s economic value (its business case) in the face of rising costs and also recommends reducing its planned maximum line capacity (from 18 to 14 trains per hour). Unless Oakervee is to be ignored, addressing these concerns will impact on decisions on Phase 2b. They were anticipated in our 2018 report Beyond HS2 and (as we shall see) both of these Oakervee challenges can be addressed.

But questions on Phase 2b cannot simply be answered by looking at a conventional/high-speed line mix as an alternative way of achieving similar aims. Instead, the remit for the Phase 2b investment has to be re-visited, and that needs to take into account shifting national priorities.

Three key issues since HS2 planning started in 2009

Planning major infrastructure projects is time-consuming, if proper consideration is given to stakeholder views and environmental impacts, as has been the case with HS2. An inevitable consequence is that the policy context for such projects changes.

Today it is recognised that climate change cannot be ignored, and that transport is the #1 problem sector. This was not the case when HS2 originated in 2009. Today it is understood that increasing the capability, capacity and use of the national electrified rail network is crucial to delivering the Government’s zero-carbon agenda. No other transport project does so much to achieve this goal as HS2.

The Department for Transport decided as long ago as November 2009 that, having worked up a scheme for ‘London to the West Midlands and potentially beyond’, HS2 should take the form of a network as illustrated above and serve the cities of Manchester and Leeds – and connect onwards to existing routes to serve the North East and Scotland.

During the following 11 years, HS2 Phases 1 and 2a progressed through the Parliamentary consent process with cross-party support, with 10:1 votes in favour. In this time-span:

- The national policy ambition for better east-west connectivity between major cities across the North emerged in 2014 (and similar aims across the Midlands soon followed);

- Serious difficulties making new train timetables work across the North frustrated the achievement of expected benefits from new train fleets and electrification and the partially delivered Northern Hub scheme. This is an ongoing concern, first apparent in 2018;

- The emergence of a consensus that ‘something has to be done’ about places ‘left behind’ Typically, these are towns, not cities, in de-industrialised and coastal areas – a pattern most apparent from the results of the General Election of December 2019, and reflected in telling observations by northern MPs, both Conservative and Labour.

The time has come to face some difficult choices. It’s worth looking at these three issues and whether and how HS2 helps. It turns out there is plenty that can be done.

1.Better east-west city-city connectivity

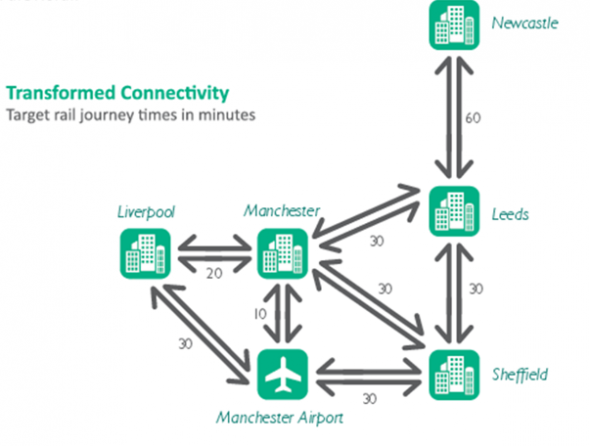

It was in fact HS2 Ltd’s Chairman, Sir David Higgins who first called for an examination of better east-west inter-city connectivity across the North in January 2014 as a complement to the north-south connectivity gains that HS2 will provide. In response, the cities of Liverpool, Manchester, Sheffield, Leeds, Hull and Newcastle came together and commissioned an initial study published as ‘One North’ in summer 2014. This study outlined ambitions for improved city-city connectivity, subject to establishing a business case.

Source: One North report, July 2014

The Northern Powerhouse concept, advanced by Treasury Minister Lord Jim O’Neill and supported by the Chancellor of the Exchequer (‘the money will be found’), was that the northern cities were geographically close to each other but operating in economic isolation because of poor inter-connectivity. If this was overcome, it would bring large economic agglomeration benefits, and create an effective national counterweight to the ‘pull’ of London.

| An early win

One northern city pair can readily be provided by HS2 Phase 2b itself (in fact the busiest city-city commuter route in the North, between Sheffield and Leeds). Greengauge 21 has long advocated that this segment of Phase 2b should be made subject to a fast-tracked powers application so that it can be opened in the 2020s. Note that it is most unlikely that the whole of Phase 2b could be progressed through a single Parliamentary Bill given its geographic spread, so priorities will have to be set anyway. A new fast link between these two Yorkshire cities could also serve Bradford and would free up capacity on existing lines serving Barnsley and Wakefield. It would entail investment in station improvements at, and on the approaches to, both Leeds and Sheffield, but this is rapidly becoming inescapable anyway. |

More ambitiously, Transport for the North, picking up on the Northern Powerhouse concept, suggested that a high-speed route could be fashioned between Liverpool and Manchester, by adding a new line from Liverpool via Warrington to the planned HS2 Phase 2b line into Manchester city centre. Links cross the Pennines (Manchester-Leeds) would require new lines that lie beyond HS2 plans. Here, there are also plans costed at £2.9bn for an upgrade to the existing Trans-Pennine line, with electrification and capacity increases, some of which are the subject of a current public consultation.

An equivalent but more modest strategy for better east-west connectivity in the Midlands was developed by Midlands Connect. This relied on lower cost measures (new connections to the planned Phase 2b line) to improve east-west connectivity, for instance between Birmingham and Nottingham, and added the idea that Leicester could be provided with HS2 services running northwards to Leeds.

On the face of it, all such plans look helpful to the HS2 business case, adding benefits that can be captured from the Phase 2b plans, with the extra costs being met by new, complementary, regionally-based programmes. But the risk was always that these regional connectivity gains become dependent on the part of HS2 (Phase 2b) for which cost estimation is least certain and delivery timescales are longest (20 years).

Re-prioritising Phase 2b (possibly with Northern Powerhouse Rail added) ahead of Phase 1 and 2a, as some have advocated, will not help the North. With no planning powers and the risk of further cost inflation ahead, Phase 2b can be delivered no earlier than the current target of 2040; and the more secure business case and advanced delivery of Phases 1/2a which bring large benefits to North West England, North Wales and Scotland, would be needlessly wasted.

2. Current problems with Rail in the North of England

The Victorian legacy of competing railway companies building their own routes to serve cities such as Manchester has, over the years since, inhibited rational development of the rail network in the North of England. Identified as the single biggest transport challenge by the Northern Way (a grouping of the Regional Development Agencies for NW England, Yorkshire & Humber and NE England) in 2007, it was to be addressed by the ‘Northern Hub’ scheme, but in practice, the original concept has only been partially completed and has left the critical Castlefield corridor hopelessly over-stretched, trying to accommodate a mix of long distance intercity, freight and local commuter services.

The Approach to Manchester Piccadilly today

Photo: RAIL

Neither HS2 Phase 2b plans nor the bolted-on Northern Powerhouse Rail (NPR) plan addresses this problem. And indeed, according to an article in the Sunday Times on January 26th 2020, the HS2 Phase 2b plan for Manchester introduces new problems of its own once NPR is added into the mix. It was reporting on the HS2 Phase 2b plan which was seen as “utterly baffling” by rail engineering experts Bechtel in a new report prepared for Manchester City Council which concluded: “current HS2 train platform designs are facing the wrong way for passengers travelling onwards to Leeds”. The Bechtel report makes clear that unfortunately the HS2 terminus platforms at Piccadilly face west towards Liverpool, so requiring a train reversal (and a 400m walk from one end of the train to the other for drivers) if trains are to continue to Leeds.

As we noted in the 2018 report Beyond HS2, the current HS2 Phase 2b scheme fails to address the problems of Manchester’s legacy rail network. We said that if it turned out that there was a problem with the business case for Phase 2b (as the leaked version of Oakervee now implies, and the Bechtel report serves to highlight) then it would be worth re-considering the Manchester part of HS2 so that its tunnelled approach to Manchester Piccadilly is from the west, rather than the south. Then it can provide a parallel route for long-distance trains, freeing up the Castlefield corridor to act as a ‘metropolitan’ (Greater Manchester and environs) facility. Such an approach would have benefits for Liverpool too, creating a way of reaching the 20 minute target city-to city link to Manchester and the prospect of a much faster connection from HS2 from the south. There was no shortage of appropriate (and some less expensive) alignments for an HS2 route into Manchester from the south when Phase 2b alignments were originally studied by HS2 Ltd.

A western approach not only engages with the Liverpool-Manchester faster connection (undeliverable under current HS2/NPR plans) it is also better oriented suitably for onward east-west trans-Pennine rail connections to both Sheffield and Leeds, overcoming the problem Bechtel identified in the Phase 2b design. And it strengthens the key regeneration ambition of the Manchester authorities for the area around Piccadilly station.

This approach would remove the HS2 station near Manchester Airport from the Phase 2b plan, saving cost. But again, as set out in Beyond HS2, there is a pressing need to resolve the current bottleneck at the terminus station at Manchester Airport which HS2 plans (unsurprisingly) don’t address. Here, most fortunately, there is a scheme available to add a western rail connection into the Airport, solving the bottleneck problem and boosting east-west rail connectivity to the North’s main airport. This scheme is ‘live’; it can be fast-tracked to boost the North’s international connectivity, and it has a long-standing protected alignment.

3. Addressing places ‘left behind’

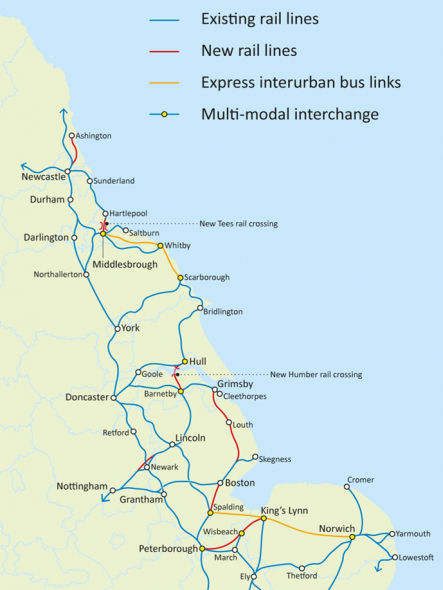

This isn’t a new problem at all, but ‘levelling up’ has gained traction and can’t now be ignored, in transport policy as well as in other respects. And there are some exciting answers available – some involving rail, others bus – as set out in a Greengauge 21 report from Autumn 2019, written for the UK2070 Commission. Schemes such as re-opening the Ashington Blyth and Tyne railway to serve former Northumberland mining villages and link them to Newcastle and its job and higher eductaion opportunities; to connect Mansfield and Kirkby-in-Ashfield with Toton and onwards to Leicester as part of a resuscitated Midland Main Line electrification project are both schemes that can be delivered in the 2020s. A wider picture for the eastern side of England is illustrated below, and this includes a mix of quick-wins from integration of express bus and rail networks, restored rail connections along with the creation of some new rail estuarial crossings that would take longer to bring to fruition. They need to form part of a coherent porgramme with short, medium and longer term deliverables.

Source: Greengauge 21 for UK2070 Commission, November 2019

Addressing Oakervee Review Report key concerns (i): scaling back from 18 trains/hour

In advocating that HS2 Phase 1 and 2a proceed, despite expressing concerns about the business case, both in terms of its benefits and capital costs, the leaked Oakervee report raises a key qualification: a recommendation to cut the planned maximum throughput of high-speed trains on HS2 into London from 18 to 14 trains/hour, which if adopted, has huge ramifications.

The recommendation is based on the lack of precedent for such a high throughput on existing high-speed lines around the world. It is a view rejected outright by former HS2 Ltd Technical Director Andrew MacNaughton. But if accepted, it means that HS2 could not support its full end-state service plan which has 11 trains/hour from the western corridor of the ‘Y’ to London and 6 trains/hour from the eastern (there is plenty of demand for the 18th path, but it is currently left ‘spare’ in the current HS2 Ltd service specification). In effect, if adopted, 14 trains/hour means the Y-shaped network doesn’t work.

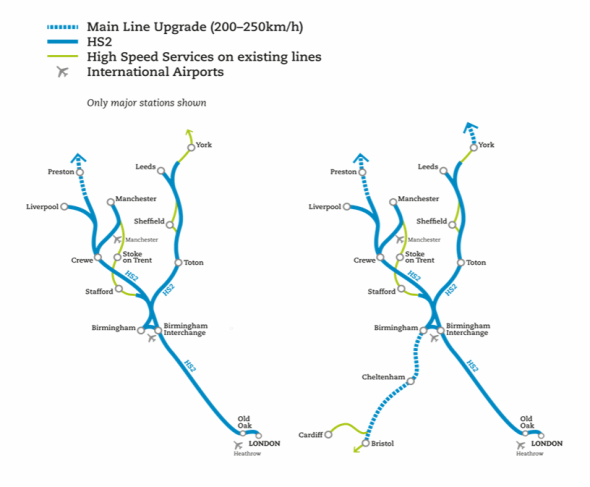

This possibility – that 18 trains/hour would come to be seen as an unacceptable risk – was contemplated in Beyond HS2 in 2018. The solution proposed in that report was that instead of a ‘Y’-shaped network, HS2 should be re-structured into an ‘X’, which allows full use to be made of the capacity of each high-speed limb, with HS2’s focus broadened away from London. Although examined (and ruled out as infeasible) in the early days of HS2 planning, the subsequent emergence of the Midland Rail Hub scheme centred on Moor Street station in Birmingham – which is effectively to be conjoined with the HS2 station at Curzon Street – makes an X-shaped network possible.

Source: Beyond HS2 Figure 10.2 ‘Changing HS2 from an X to a Y shaped network’; Greengauge 21, July 2018

This approach re-purposes the HS2 eastern limb as primarily an inter-regional route (serving cross-country services on a Newcastle-Bristol axis), although it would still be capable of supporting the planned fast Leeds-London HS2 service. Speeded up Newcastle-London trains would use an improved East Coast Main Line rather than travel over HS2 via Birmingham.

The message is this: either the eastern limb is re-purposed as suggested here, or it will (with a 14 train/hour cap) likely founder with insufficient benefits to justify its completion.

Addressing Oakervee Review Report concerns (ii): can the business case be improved, and costs reduced?

In a 14 train/hour world, some of the Oakervee concerns on project costs and benefits can be addressed. Provided a firm planning decision is made on this question, it is possible to make big savings, because the scale of London HS2 station facilities can be cut back. The argument that London needs two HS2 stations falls away.

One possible option that would merit immediate consideration would be as follows:

- Old Oak Common station cut back from its current all-HS2 trains stop format with 6 high-speed platforms to a simpler, user-friendly, (and operator-friendly) design, with a single platform in each direction and through lines for non-stopping HS2 trains – a service mix that is only possible with a less intense HS2 service headway. This means:

- A large capital saving at Old Oak HS2 station

- A capital saving (for a scheme that is not yet funded) for a major station on the Great Western Main line (the station would only be provided for the Crossrail tracks rather than a presumption that all Paddington services would stop at Old Oak)

- With a smaller station foot-print, a release of land for more housing development on the Old Oak Common development site which would still be served by Crossrail

- With say 10 out of 14 HS2 trains each not stopping at Old Oak, a speed up of c5 minutes for most HS2 trains

- An equivalent saving for Paddington services where long distance trains (from Cornwall, Cardiff etc) would not need to have journeys slowed down by c5 minutes to call at Old Oak

- Relief of the single greatest operational pressure on the HS2 system

- Phase 2 of Euston HS2 station dropped, saving a lengthy period of service and local disruption through the 2030s.

Together these are scope changes that would bring significant cost savings and benefit enhancements, strengthening the HS2 business case. But they cannot be captured if the question of maximum long-term line design capacity is left vague and open: it is a clear and present strategic choice needing a decision now.

Conclusion

Given concerns over HS2’s budget, it is perhaps understandable that Oakervee would call for a review of Phase 2b, while signalling that Phases 1 and 2a should proceed.

But a review of whether there are cheaper ways to achieve the original objectives of HS2, delaying progress with Phase 2b while the examination is underway, is pointless. The options have already been studied and we know that they would entail undue disruption to existing rail users (and adjoining properties) for many years because of the scale of enhancement needed to the existing network.

A new Phase 2b mandate needs to be set, one in which the regions are invited to examine the choices available, with a remit to look at (i) east-west connectivity (as well as north-south) (ii) measures to tackle today’s key rail network constraints (iii) serving towns as well as cities beyond the new HS2 infrastructure, including explicitly the need to consider places ‘left behind’ and (iv) delivery of improved inter-regional (cross country) links.

The aim must be to develop a phased programme with deliverables in the 2020s as well as later, and we have pointed out several such projects that can be sensibly accelerated for early delivery. The Leeds-Sheffield HS2 link should be one such accelerated scheme.

© January 2020, Greengauge 21, Some Rights Reserved: We actively encourage people to use our work, and simply request that the use of any of our material is credited to Greengauge 21 in the following way: Greengauge 21, Title, Date