“On 25th March 1807, a year after the Swansea-Mumbles line started transporting cargo, the railway began to also start transporting passengers.

Benjamin French was the man who brought about the world’s first passenger railway by converting an iron carriage to be fit for transporting people. He was an entrepreneur from Morriston who thought that people would enjoy travelling by train for the romantic scenery of the Mumbles.

One of the original investors in the idea, he began to advertise this new found service after agreeing to pay the owners £20 a year for its use. The service was such a success that they immediately upped their offer to £25 so that they could continue using the service.”

The railway closed some 60 years ago, after operating as successful modern segregated tramway for many years.

Metro plans

‘Metro’ plans have already been developed for South East Wales (Cardiff, Newport and the Valleys), and although on a different scale, also for North Wales. In each case, comprehensive plans centre on rail proposals and bus services. In the South East Wales case, work is underway to electrify some sections or routes and to introduce a tram-train operation to serve Cardiff Bay and the Senedd (Wales Government).

Regional local authorities are now turning their attention to Swansea Bay and West Wales, to examine the best way to create a Metro network for the area and a public consultation on options is underway.

Wales Government’s Transport Strategy, March 2021 and the National Plan 2040

These two documents published in 2021 by the Welsh Government are closely inter-linked. The transport strategy commits to increasing the proportion of active travel and public transport use from 32% to 45% of all travel by 2040.[1] The strategy document says:

“Over the next five years we will … deliver our public transport Metro systems in all parts of Wales to improve services and better integrate other public transport and active travel with the rail system”.

The over-arching aim is to help fulfil the Welsh Government’s explicit social well-being targets. Swansea Bay and West Wales will need to offer a much better alternative to car use as will other parts of the nation. And, consistent with the new 2021 Strategy, plans will also have to reduce the need to travel.

While no doubt some parts of a Metro concept could be delivered for Swansea Bay and West Wales in a 5 year time-span, here we look at options which would inevitably have a longer implementation period.

Swansea Bay and West Wales

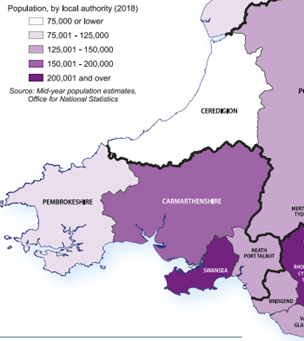

The National Plan usefully delineates Swansea Bay/West Wales and shows the distribution of population (as of 2018):

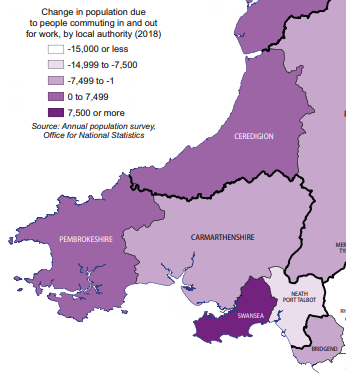

The current pattern of commuting into the Swansea area is illustrated in the following diagram, also taken from the National Plan 2040:

As the 2040 Plan makes clear, recent trends in rail use and rail investment in Swansea Bay/West Wales are not propitious:

“The number of train journeys made in Wales increased by 30% between 2007-08 and 2017-18. The vast majority of this increase was in journeys starting and/or finishing in the south east. The Wales Route, which represents 11% of the UK rail network, has received just over 1% of rail enhancements in recent years.”

Indeed, rail use over the ten year period to 2017/8 scarcely grew in West Wales.

The National Plan sets out something England lacks: a spatial strategy. This is hugely helpful in seeking to set transport priorities. For the southern part of Wales, the updated spatial strategy is shown below.

(reproduced from the Wales National Plan 2040)

It can be seen that Swansea and its hinterland is designated as a national growth area (cross-hatched) – alongside a much more extensive growth area in South East Wales. Linkages westwards into Dyfed (‘The South West’) and eastwards from Swansea Bay along the heads of the valleys corridor which forms the northern boundary of the SE Wales growth zone, are each identified as being ‘national connectivity’ linkages (as is a connection to the national airport at Rhoose). The Heads of the Valleys corridor is the subject of a major highways improvement programme with an innovative financing regime (A465), but the project runs out at Hirwaun, as it leaves South East Wales.

Part of the regional connectivity component of the Future Wales spatial strategy is Metros: South East Metro, South West Metro and North Wales Metro. These are designed to “create new integrated transport systems that provide faster, more frequent and joined‑up services using trains, buses and light rail.” This reflects a focus on planning for growth in urban rather than rural areas in Wales and adopting a [city]/town centre first policy.

“The Welsh Government promotes transit orientated development, focusing higher density and mixed-use development around public transport stations and stops. The metro projects, which are at different stages of progress, all offer significant and timely opportunities to identify locations for transit orientated developments around new and existing stations. Land in close proximity and with good access to metro stations is an important and finite resource and will play a key role in delivering sustainable urban places.”[2]

The report explains that the regional local authorities are consulting on Metro options for SW Wales, and these will include consideration of:

- Increased South Wales Main Line services to Carmarthen, Pembroke Dock/Milford Haven

- An examination of the potential for a strategic West Wales parkway station

- An examination of the case to re-open various closed lines including in the Dulais, Amman, Neath and Swansea Valleys.

The South Wales main line itself is seen as needing to adopt the EU’s TEN-T standards, with higher operating speeds and electrification.

Swansea Bay and West Wales Metro

Any review of transport options in 2021 faces two stark realities:

- The Covid-19 pandemic creates uncertainty about future travel demand patterns, especially for office-based journeys to work;

- There needs to be a dramatic reduction in carbon emissions from the transport sector.

On the Covid-19 point, the employment base in Swansea Bay is diversified. Many jobs are not office-based and hopefully will remain intact and on a not very dissimilar basis post-pandemic. These would include, for instance, jobs in the higher/further education sector, those based on the recreation, hospitality, tourism and leisure sectors, as well as those in industry, where the scope for work-from-home during the Covid period has been very limited. The long-term aspirations of the Spatial Strategy call for a city centre renaissance, post pandemic which becomes unsustainable if it is not led by active travel and public transport.

The carbon emissions driver is less severe in Wales than across the UK as a whole. Transport which accounts for over 30% carbon emissions UK-wide, accounts for only 16% of greenhouse gas emissions in Wales. Nevertheless, it has to be recognised here that, as elsewhere, diesel powered rail systems have a limited shelf-life. This will likely be confirmed in DfT’s national decarbonisation strategy expected to be published in May/June this year.

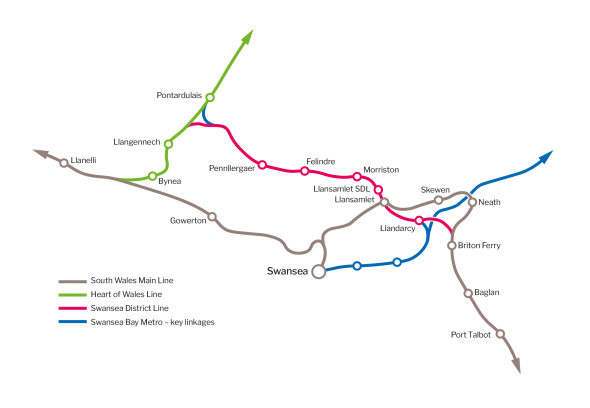

Network Rail has already prepared a decarbonisation strategy and it identifies the South Wales Main Line from Cardiff to Neath, Swansea, Llanelli and Carmarthen, along with the Swansea District Line[3], as routes that should be electrified. Other lines (west of Carmarthen, the Heart of Wales line and the various freight-only lines) would be expected to see services provided using battery or hydrogen power.

A recent review of rail electrification schemes focused on rail freight pointed out that while significant progress is being made in developing electrically powered vans and medium sized goods vehicles suitable for logistics/delivery within a 100 mile range, there is no viable re-powering option available for long-haul HGV movements that are currently diesel powered.[4] This led the review’s author to conclude that in South Wales, it would be worth extending the current electrification limit westwards as far as Swansea, picking up freight flows from Port Talbot ‘under the wires’. The reality is that the more distant parts of Wales need an electrified or part-electrified railway to overcome the long distances for which there is no suitable road-based alternative to diesel for freight (HGV) haulage.

Given the high capital cost of electrification – to be considered alongside the significant carbon gains it brings, especially if passengers and freight can be attracted away from less carbon-acceptable means of travel –it makes good sense to aim for full utilisation of routes that are electrified, seeking to increase the share of travel made by (electrified) rail. This would apply to the South Wales Main line.

The South Wales Main Line

There are important inter-relationships with adjoining sub-regions that will have a bearing on future Swansea Bay/West Wales train services. Decisions to invest in the rail network of South East Wales, and in the Newport-Crewe, Severn Tunnel Junction-Gloucester/Bristol lines are likely to be crucial to the Swansea Bay/West Wales area rail network.[5]

A key question for the Swansea Bay area is whether it wishes to be part of a wider economic growth zone extending eastwards through Cardiff to Bristol. If it does, as suggested in the National Plan 2040, then one priority should be the provision of (at least) hourly fast services between Swansea Bay key stations, Cardiff and Bristol. Swansea Bay can enhance the prosperity of this multi centred corridor, adding travel demand attractions and supporting the prospect of office-based employment switching post-Covid-19 to a 2-3 days/week, longer distance, commuting pattern.

While, a few years ago, the Welsh Affairs Select Committee was persuaded that electrification of the Swansea-Cardiff line would bring only minimal journey time savings, it noted that there would be localised air quality gains, and that electrification could allow more local (’Metro’) services to be operated.[6] The Committee also noted that hybrid electric+diesel trains have a limited shelf life and it is encouraging to see that Hitachi is now going to trial a battery-electric version of its GWR intercity trainsets, which could allow the replacement of diesel engines with battery packs in due course. This might be combined with some amount of ‘discontinuous’ electrification, but the level of use of this Main Line and its mix of traffics should justify its electrification as a priority.

Swansea District Line (SDL)

The very lengthy travel times by rail from, for example, Cardiff to Tenby (close to 3 hours, usually with a change of trains en route), make rail uncompetitive compared with car travel, and so any facility that shortens rail journey times has some appeal for longer distance services to/from West Wales. The Swansea District Line acts as a cut-off route between Port Talbot and Llanelli, used for a modest number of freight movements currently (from the oil terminals at Milford Haven and from Trostre steel works at Llanelli). The time saving it offers for passenger trains between Cardiff and Llanelli/West Wales come at the price of not serving Swansea and Neath. But, inevitably, trains operated over the SDL need to be additional to those serving Neath and Swansea and demand take-up is likely to be thin having missed these major intermediate generators of demand. The case for electrification of the line would be weak.

The reality is that both freight and passenger services to/from West Wales can avoid the need to call into Swansea High Street and reverse without using the SDL by using the through line at Landore. This would also save some time for West Wales users and (unlike the SDL route) would retain a station call at Neath. Unless a good proposition can be identified to increase use of the SDL, with budget pressures on the national rail network, a good case could be made to close it, given its limited value. So what are the other options?

The consultation paper identifies a set of options that could make use of the Swansea District Line, which pre-Covid carried just one passenger train/day. One is the idea of a parkway station at Felindre on the SDL, seen as parkway-style station to serve the wider Swansea area. To be effective, this facility would need, at the very least, an hourly train service. One option might be an extension of the hourly Paddington train which otherwise terminates at Cardiff, to provide some speed-up for Llanelli, Carmarthen (and possibly other locations in West Wales). But the time savings available are modest – of the order of only 10-15 minutes – over a train that calls at Neath, Swansea (reverse) and Gowerton. It is hard to see the case for a Parkway station on a route that today can only support a single train per day.

There is also a suggestion that a set of local stations could be provided on the SDL, allowing a Swansea Bay service to operate from Ammanford and Pontarddulais to the city centre at Swansea. Following the consultation document, this would reach Swansea by using an extant freight route via Llandarcy, approaching the city centre ultimately from the east, necessarily operating tramway style (for which some future provision has been made) rather than a fully segregated railway over the final section into the city centre. There are some parallels with the arrangements devised for the Cardiff Valley line metro service to serve the Senedd in Cardiff Bay.

The closure of local railway lines that could have provided useful routes from the valleys to the north into Swansea city centre is an unfortunate historic reality. Using the Swansea Direct Line to support a local Metro service requires investment to overcome this legacy. But it could be used to connect Pontarddulais (and beyond it Ammanford and Pantyffynon with a set of new stations along the Swansea District Line, as shown in the diagram below. These stations are at Penllergaer, Felindre, Morriston, Llansamlet and Llandarcy, together with two suitably located stations along the eastern seaboard approach to Swansea city centre. A park and ride facility at Felindre for local (Metro) travel could form part of this approach.

Source: Consultation Paper – route from Neath Riverside/Llandarcy to Swansea (in blue) added by Greengauge 21

This would be a major scheme and the business case would rest on the availability of otherwise unused railways. To keep costs manageable, it would very likely to be necessary to stop using the District Line for any non-Metro (light rail) purposes (but as we have seen, this should be no great loss). The SDL would be removed from the National Rail network.

Tramway style stations could be well integrated with local development and avoid the very substantial costs of disabled access compliance.

Having created a new line into Swansea city centre, it is worth considering what other use could be made of it.

Connections with South East Wales

The consultation paper also identifies the possibilities of potentially linked further developments to restore rail-based passenger services that extend into SE Wales:

- A re-instated link between Hirwaun and Cwmgwrach;

- A new service from Cwmgwrach to Neath (this is a little used freight line currently, along the Vale of Neath); and

- A tram-train style operation from Neath/Llandarcy to Swansea city centre.

Taken together, these three linkages could form a valuable new rail connection, improving accessibility to the former Swansea eastern docks area and opening up the scope for direct through services between Swansea, Neath, Hirwaun, Aberdare and Pontypridd. These services would share use of the new light rail route into Swansea city centre from the Swansea District Line; east of Llandarcy, they would use existing limited use freight-only lines as far as Cwmgwrach, after which point a new alignment would be needed to reach Hirwaun. Beyond this point, there would be connections into the SE Valley network, including bus links using the upgraded A465. The first section of this line (from LLandarcy through Neath) is also shown in the sketch diagram above.

The creation of some equivalent operating concepts in South East Wales, including the deployment of tram-train type vehicles, helps de-risk this proposition. Its development here would require joint planning across the two adjacent southern Welsh Metro planning regions – and there is an obligation to do just this contained in the Future Wales 2040 plan. It would be a scheme unlikely to be prioritised by either region acting alone but could bring significant benefits looking at the two regions together.

Faster connections for West Wales

Electrification of Cardiff-Swansea may help take a few minutes out of journey times. And whether electrification needs to extend further west – say to Carmarthen – will need investigation, ultimately very likely to be determined by the range limits of battery-electric powered trains. The beneficial impacts of electrification are likely to be larger on sections of track with steep gradients (the approaches to Swansea, for example) and if older diesel units are replaced with new battery electric trainsets.

Another possibility is avoiding Swansea and Carmarthen, both of which lie off-route and can only be served with reversals, probably worthwhile only for selected trains through the day.

As demand builds over time and provided line capacity constraints don’t preclude it, Swansea could get a faster connection to Cardiff and London if the intermediate stops at Neath, Port Talbot and possibly Bridgend are omitted from the hourly GWR service. This would be complemented by an extension of the hourly Cardiff-terminating GWR London service which would call at Bridgend, Port Talbot, Neath, Llanelli, Pembury & Burry Port and Carmarthen.

Conclusions

The electrification of the Cardiff-Swansea line should be seen as a renewed priority. In conjunction with electrification of the relief lines though Newport and electrification to Bristol Temple Meads, a high quality frequent Swansea-Neath-Port Talbot-Bridgend-Cardiff-Newport-Severn Tunnel Junction-Filton Abbey Wood-Bristol Temple Meads service should be established to form the backbone of an economic prosperity arc across the Severn Estuary.

Using the Swansea District Line for a Metro service requires creates new connections and would support multiple development opportunities at a set of new local stations. Without a new connection, the east-west orientation of the line frustrates its potential role as a useful metro-style line between the Amman valley and Swansea.

Connections from the Swansea Bay area to South East Wales could be improved significantly by the re-creation of the link between Cwmgwrach and Hirwaun.

The Swansea Bay Metro could use the same technology that is being developed for tram-style operation into Cardiff Bay to provide access to Swansea city centre from key valley towns such as Pontypridd and Aberdare.

Given where passenger railways started 214 years ago, someone is bound to ask whether the light rail into Swansea city centre could be extended to Mumbles. That is a challenge we leave for others to ponder.

References

[1] https://gov.wales/llwybr-newydd-wales-transport-strategy-2021

[2] Source: National Plan 2040 p86

[3] Its inclusion is no doubt based on its designation as diversionary route. Its regular but limited use for freight trains (oil traffic, mainly) and minimal passenger services would not otherwise justify the capital investment of electrification.

[4] Julian Worth Freight Electrification: making it happen, Modern Railways, April 2021 p75

[5] Some of these propositions are being considered in the current Union Connectivity Review

[6] Electrification would allow some journey time gains and this would apply especially if older diesel units were replaced by electric units to provide local/Metro services. This would also help get the best use out of line capacity where a mix of stopping and longer distance services operate. In this way, electrification can be seen to bring a capacity (as well as carbon and air quality) benefit