For 15 years, a Government consensus held. The West Coast Main Line was the priority corridor for capacity relief in the form of HS2.

Now, with the section across Cheshire abandoned and completion to Euston fogged by the miasma of a private sector finance requirement, the way forward for the west coast has become unclear.

Here’s some background and lessons from the line’s history.

Electrification 1962-1974

The value of the West Coast Main Line (WCML) to the nation was recognised in the British Rail(ways) era through the commitment to a staged electrification programme. This would take over a decade to complete. A full set of mitigations came into play, with services diverted on to alternative routes to London (St Pancras/Paddington). Locomotive changes took place progressively nearer to London as the 25kV overhead was installed and energised starting from Manchester, progressing north to south.

As ever with a HQ based in London, for the British Railways Board (BRB) there was less conviction about the northern part of the WCML from Crewe to Scotland. Senior BRB managers could be heard to mutter ’more sheep than people up there’. But while coming eight years later in 1974, the Anglo-Scotland electrified services were a success too.

Passenger demand blossomed, with faster journeys over systematically modernised and more reliable infrastructure. Freightliner services blossomed too.

Three interesting lessons can be gleaned from travel market behaviour in response to electrification of the west coast in the 1960s/70s.

- The travel market proved to be elastic

The introduction of fast, frequent and comfortable services between London and the major cities in the Midlands, the North West and Scotland, backed with strong marketing of the InterCity brand, showed just how elastic – how responsive – this type of travel market could be. Good encouragement for the ‘125’ revolution set to follow soon afterwards on the western and eastern regions.

- Large-scale mode switching

The second lesson: roughly half of the new demand and revenue generated came from those transferring from other modes of travel to the new, electrified train service – mainly from car, but also coach and, in some cases, air. The other half of the increase was ‘induced’ demand: people who, absent this fine train new service, would not have made the journey at all. Those counting the extra revenue into the BRB account didn’t mind the source, but the valuation of economic benefits of diverted and induced demand differ. Those transferring from road also bequeath a measurable reduction in road traffic – so less congestion, fewer accidents, less pollution. Induced demand brings wider economic efficiency benefits.

- Shorter city-city connections in the regions: not so much

Although the link between the two largest provincial cities Birmingham-Manchester also got a new electrified service with an accelerated, regular interval timetable, the demand uplift was disappointing. The truth is that rail offers an outstanding advantage over the alternatives for travel to/from London, but this advantage is not shared so much by rail services elsewhere. In the Birmingham-Manchester case, few journeys are between the two city centres, and neither city can offer the comprehensive onward rail connections available in central London

The 1980s

By the 1980s, the 110 mile/h west coast accounted for fully 37% of InterCity business sector revenue. But here, where APT had once tantalised only to be denied, there was to be no electric HST instead. The scope to cut journey times on the west coast without tilt, but with speed increased to 125 mile/h where line geometry would allow, would only take 15 minutes off London-Manchester journey times at best.

The challenge was how to bring InterCity on the west coast up to scratch, on a par with its long distance neighbours. Long deferred infrastructure renewals would have to be addressed. Thirty years later, was like-for-like replacement the best that could be hoped for?

Route Modernisation 1997-2003

Uniquely, those bidding for InterCity West Coast, the final franchise to be let, were offered a choice. Take on the existing, now rather tired, part of InterCity, and soldier on with ever older assets; or buy into a major route upgrade. Those bidding would need to price both options. The office for rail franchising (OPRAF) would choose whichever bid offered best value for money – the biggest premiums.

For Richard Branson’s Virgin Rail Group, bidding for a railway in decline had no appeal. An upgrade approach was a different matter. Tilting trains at an enhanced speed of 140 mile/h, would be made possible, Railtrack proposed, by a new train control system unique to the WCML. Just two and half years later, in December 1999, Network Rail would admit this was, in fact, undeliverable.

By then the 140 mile/h Pendolino fleet was contracted, and the railway was committed to tilt but would need to limit speeds to 125 mile/h. This wouldn’t require the radical new train control system, but instead a Tilt Active Supervision System (TASS) would be provided. Network Rail would still have a huge upgrade programme to deliver, although much of the work and cost was in fact attributable to long overdue renewals.

The Advanced Passenger Train (APT) in 1981 and the Pendolino, 22 years later

Photo Greengauge 21

The upgrade approach would turn out to be the ultimate test for the new privatised railway regulatory architecture. While OPRAF had pre-agreed with Railtrack the terms of an upgrade package, it presented Virgin with two immediate problems.

The first centred on legal realities. If Railtrack failed to deliver the OPRAF-specified upgrade in full and on time, the train operator (Virgin) would still face its franchise obligations (££ premiums growing year-on-year and payable to OPRAF). And with much of the detail of the programme yet to be developed, some of its delivery was inevitably at risk. Railtrack would do their best of course, but if something proved more expensive than they had budgeted, or not do-able in the agreed timescale, what then?

The second problem is of wider relevance to all longer term franchises: year-on-year growth in rail passenger demand ultimately creates a capacity challenge. Tweaks to the train service offer, for instance by increasing the number of seats available, only get you so far.

Virgin Rail Group (at the time, alone it seemed) understood this. A transformed west coast service was forecast to treble passenger volumes within 15 years. Faster services (tilt at 125 mile/h, cutting key journey times by 30minutes or so), would need much more capacity. The elasticity evident in the west coast rail travel market hadn’t ended in 1974. Better services would draw more passengers. The upgrade agreement with Network Rail would have to reflect this reality. More train paths would be needed and a significantly expanded and fully-funded infrastructure plan would be required.

This didn’t happen without controversy. Those with franchises let on a plain vanilla basis looked on in envy. The Rail Regulator was presented with a new fully worked-up access agreement between Virgin and Network Rail, known as ‘passenger upgrade two’(PUG2). It would provide for a big increase in intercity west coast train paths into Euston, with Virgin funding its share of capital works designed to support not just tilt, but higher service frequency, the latter being a feature almost entirely absent from the original OPRAF-Railtrack agreement (‘PUG1’). And, following last minute representations to the ORR by the rail freight companies, a further obligation arose for Network Rail: the railfreight companies demanded and got an extra 42 freight paths/day as part of the West Coast Route Modernisation (WCRM).

Despite their best efforts, Network Rail could never quite produce a timetable that added intercity capacity, and protected all other franchisee rights, and provide this scale of freight capacity expansion. There were always 20-25 ‘misdemeanours’ as Network Rail’s Robin Gisby would say (the lawyers would have said ‘non-compliances’) in each draft timetable. The position would have been even worse if Network Rail hadn’t ditched 140 mile/h operations.

SRA oversight and resolution

It would take an industry guiding mind to resolve matters. Fortunately, back then, one had just been created: the Strategic Rail Authority.

With no process available to mediate between operating companies, the SRA – which inherited responsibility for franchise oversight from OPRAF – took charge of setting out a whole-route timetable. The SRA approach was back to basics: on the graph first would go the long distance InterCity Pendolino and long distance freights paths. The SRA had contractual clout with franchisees and the expertise needed to devise a satisfactory overall outcome.

The SRA decided on a 20-minute interval service for Birmingham-Euston and Manchester-Euston. This broke the 15/30 minute cycle of local services on the Coventry corridor into Birmingham. These are tough calls to make, exposing the limits of what can be done with line of route of enhancement. Four-tracking the Coventry Corridor was not a viable option. But InterCity West Coast would ultimately achieve its long term forecast, trebling demand.

Over the length of the route, renewal and enhancements were blended into a major capital programme. In many ways it was the pinnacle of achievement of the privatised railway: enhancement with new sources of funding from a franchise operator committed to transforming a tired part of intercity into a growth machine. And of course, at that stage, Network Rail had its own borrowing powers.

But early upgrade works went badly wrong. Weekend possessions at Euston and then at Rugby over-ran badly, disrupting services into the following working weeks. From these embarrassing days of failure, many were quick to conclude that major route upgrades in general were best avoided.

Yet later works – Trent Valley 4-tracking, for example – while requiring planning consents and acquisition of adjoining land, progressed well, with much more acceptable delivery in terms of budget and timescales.

The truth is major upgrades are harder to implement at major nodes on the network than along plain line sections between these nodes. Careful planning is necessary and priceless.

Intelligent ways to free up line capacity for more efficient line-of-route works were needed. And at the SRA, Stuart Baker pushed for such measures: a mini-electrification scheme (Kidsgrove-Crewe) to create a temporary bypass; and Project Rio, to switch Manchester-London trains to operate via Derby and into London St Pancras instead of Euston. A re-design of the key intersection at Rugby with full route selection flexibility was disruptive to create, but destined to pay dividends for decades to come when renewals fell due.

Network Rail’s WCRM ultimately cost around £9bn. Much of this was spent on long-deferred renewals, but it was still a lot higher than had been costed originally.

And one crucial part of the Route Modernisation project was lost. ORR’s 2003 Network Rail periodic review failed to authorise funding for the planned ‘Stafford cut off’. This would have created a new railway bypassing the bottlenecks through Colwich Junction, Shugborough and Stafford – a critical omission that has come back to haunt us, twenty years later.

High Speed Two

As the UK’s busiest main line, the West Coast is also said to be the world’s busiest mixed traffic railway. So what next?

HS2’s origins in fact lay on the East Coast. By December 1999, it became known that Virgin Stagecoach was going to bid a 20-year extension to the original seven-year GNER franchise. Ultimately, Sir Alastair Morton, Chair of the Shadow SRA, awarded an extension to the incumbent, Sea Containers Ltd. But he was impressed by Virgin Stagecoach’s bid which had included a proposal to create a new high-speed line. This audacious approach drew on Virgin’s experience with the west coast. With a long term bid and growth expected year-on-year, passenger carrying capability and line capacity are ultimately going to become limiting factors. A new high-speed line on the East Coast would help create the extra track capacity needed – as well as speed up services and drive revenue growth.

And so while declining this offer for high-speed on the East Coast, Morton called for a wider study of north-south capacity needs. The resulting study was carried out by Atkins for the Shadow SRA in 2000-01, and ultimately gave birth to HS2 on the west coast.

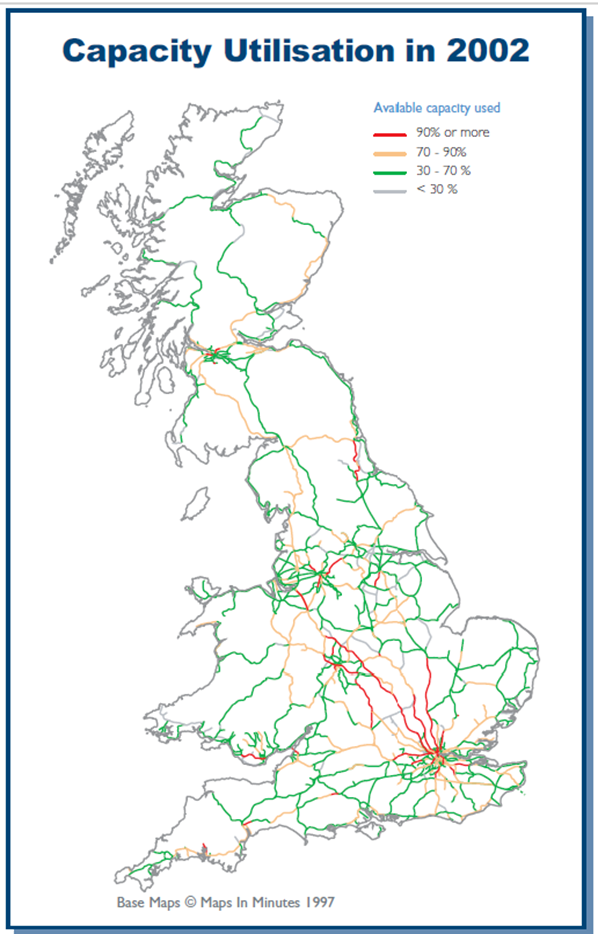

The Atkins study was required to look across all of the transport modes and all of the possible solutions to address expected demand growth in the longer term. High-speed rail turned out to be the best of all options available – better than a motorway widening programme or expanding existing railways, for example. The study suggested that by the mid-2020s, the West Coast Main Line would be saturated; the East Coast would follow not many years later. High-speed rail was all about the need for more capacity from the start.

Rail Network Capacity – the national picture

Source: Network Rail, as shown in the SRA’s Capacity Utilisation Policy 2002.

The Atkins work was quietly published by DfT in January 2004: Secretary of State for Transport, Alastair Darling, didn’t see it as a priority. By the end of 2005, in any event, the SRA had been wound up.

Greengauge 21 was set up in January 2006 and published a manifesto, sent to all MPs. With the channel tunnel rail link nearing completion, it suggested a plan was needed for a national high-speed rail system. In June 2007, it suggested where to start, in a report entitled High-Speed Two: a Proposition by Greengauge 21, which proposed a new high-speed railway linking London, Heathrow, Birmingham and the North West.

It was the Conservative Party that first picked up on this proposal, committing when in opposition to a high-speed line connecting London, Birmingham, Manchester and Leeds at its annual conference in September 2008 – a dramatic time when the global financial crash was sending shock waves across the Atlantic.

This move by Her Majesty’s Opposition prompted Lord Andrew Adonis to establish HS2 Ltd in January 2009, with a remit to develop a first phase of HS2, a route between London and the West Midlands and potentially beyond. The line would run from Euston in London to Birmingham (Curzon Street) and to Handsacre, where a connection would be made with the West Coast Main Line. The ensuing 2010 general election was won by a Conservative/Liberal Democrat coalition, which, after due consideration, decided to push ahead and seek Parliamentary Powers for HS2. Opposition was local, while all of the political parties agreed it was an investment the country needed.

In March 2014, Sir David Higgins became Chair of HS2 Ltd. He quickly saw that it would be wise to separate out and accelerate delivery of the easier, southern part of the planned second phase of HS2: an extension from the Midlands into North West England at Crewe. This would provide the long-missing Stafford cut off, abandoned twenty years ago as part of West Coast Route Modernisation: finally, it would be built. But not as once imagined. Now it would be built for high-speed and delivered at the same time as Phase 1. What had been severe limitations on pathing new high-speed services though junctions at Colwich and Stafford if Phase 1 had been delivered on its own, were significantly eased with Phase 2a in play.

Colwich Junction, West Coast Main Line

Photo: Greengauge 21

And now?

We have a problem. Curtailing the wider ambitions of HS2 (its eastern arm, for instance) is one thing. But putting on hold plans which have been granted Parliamentary approval, where land has been acquired, all the detailed environmental studies carried out, and construction lined up and ready to go (Phase 2a and Old Oak Common-Euston) is another matter.

A failure to complete the HS2 line, at least from Euston to Birmingham and Crewe, would mean that HS2 cannot fully deliver its expected economic and decarbonisation benefits. It cannot help re-balance growth prospects across the regions either. And the capacity needed to fulfil recently published Government growth plans for railfreight, which relies on the West Coast Main Line as its busiest artery, will not be met, damaging international trade, adding to logistics costs and motorway traffic overload.

A half-built HS2 is a liability for the national rail network and it’s bad news for the national economy too. Nobody wants this. It is to be hoped that common sense will prevail.

Jim Steer, Director, Greengauge 21

A version of this article appeared in RAIL issue 1009

We actively encourage people to use our work, and simply request that the use of any of our material is credited to Greengauge 21 in the following way: Greengauge 21, Title, Date.